Lammy: It's Christian to scrap a jury... but the Bible promotes due process and courts are sat idle?

Curbing of jury trials to obtain quicker justice is Christian suggests Lammy. Whilst yes the Bible stresses justice, it also includes following due process, as does our Magna Carta of 1215.

In an era where secular governance is meant to ensure impartiality and evidence-based decision-making, the intrusion of personal faith into public policy raises alarming questions. Recent statements from high-ranking Labour government officials highlight a troubling trend: using religious beliefs as a justification for sweeping undemocratic reforms. This approach not only risks incompatibility with the principles of neutral policymaking but could also sow seeds of internal conflict within the party, leading to inconsistent and potentially harmful legislation for the country.

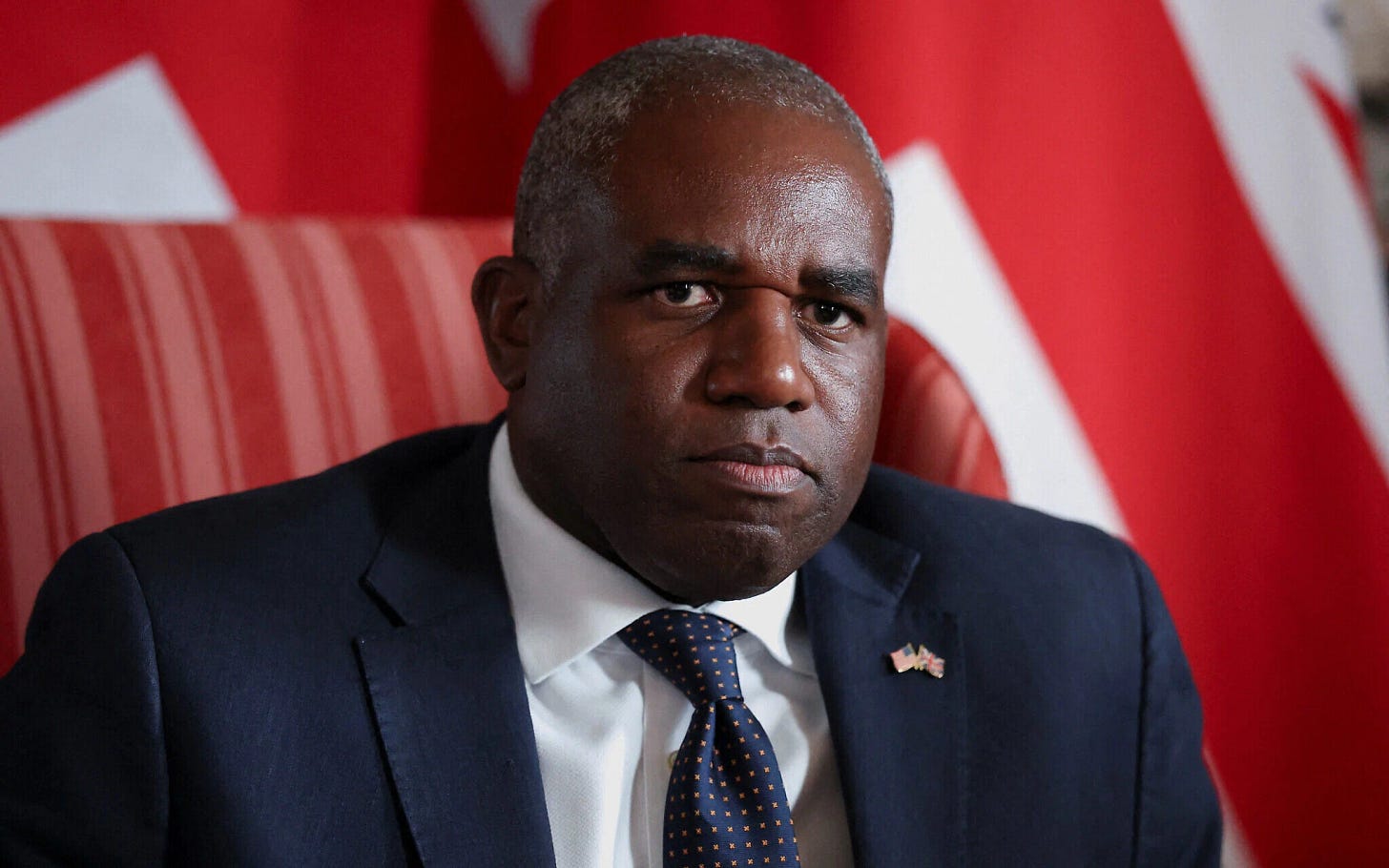

At the heart of this issue is Justice Secretary David Lammy’s defence of curbing jury trials, explicitly tied to his Christian faith, and similar sentiments from Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood regarding her faith in Islam that drives everything she does.

Lammy’s Faith Fuelled Assault on Jury Trials

David Lammy has openly stated that his Christianity guides his push to limit jury trials for certain offences, framing it as a victim centred approach inspired by biblical principles of justice and mercy. In a BBC interview, he explained how his faith helps him “see the face of the victim,” citing examples like bereaved mothers waiting years for justice in knife crime cases. While yes we agree prioritising victims is right, anchoring such a fundamental change in religious conviction is deeply problematic and the Bible also stresses a fair trial. Government policy should be rooted in data, legal precedent, and public consultation, not personal spiritual insights accepting one passage of text but ignoring another for convenience. This sets a dangerous precedent where faith supersedes rationality, potentially alienating those who don’t share the same beliefs and undermining the secular foundation of UK law.

Faith Lead Decision Making Equals Bad Policy

The issue extends beyond Lammy. Shabana Mahmood, now Home Secretary, has repeatedly emphasised how her Islamic faith is “the core of who I am” and drives her to public service. She has described her religion as the “centre point of my life” that motivates her policy decisions, including tough stances on immigration. Mahmood insists her faith guides her toward serving the country without sectarianism, but when multiple officials invoke different religious frameworks, Christianity for Lammy, Islam for Mahmood, the potential for conflict of interests and bad law is evident.

Imagine a scenario where Lammy’s Christian inspired mercy for victims conflicts with Mahmood’s faith driven emphasis on strict immigration controls or sentencing guidelines. Such divergences could result in fragmented policies, where laws are shaped more by theological interpretations than by cohesive strategy. This isn’t just hypothetical; it will produce bad legislation that prioritises individual faith opinions over effectiveness, eroding public trust in a government meant to represent all citizens, regardless of faith.

Our Courtrooms Are Empty

Shadow Justice Secretary Robert Jenrick has provided a sound counterpoint, highlighting practical solutions over faith based rationales. He points out that on various days, 70, 75, or even 81 courtrooms sit empty across England and Wales, a clear sign of underutilisation that could address court backlogs without dismantling jury rights.

Instead of invoking religion to justify removing justice that been in place for 800 years, the government should redirect funds to get these empty courts operational around the clock if that is what is needed to bring fair justice to all citizens.

This ties into broader fiscal mismanagement by Labour. The UK spends approximately £10 billion on immigration EXCLUDING court costs and appeals. Exactly why should billions be used for this, more funnelled abroad in aid, billions more into migration support, all while our own domestic justice infrastructure giving British people the basics of a fair trial be withdrawn? Reallocating even a fraction could fund judges and juries, ensuring fair trials for the accused, victims, with justice for families, without scrapping centuries old safeguards.

Why Jury Trials Matter

Trial by jury isn’t a modern convenience; it’s a cornerstone of English law dating back to the Magna Carta in 1215, designed to prevent biased decisions by local lords or authorities. Over centuries, it evolved to ensure impartiality, with jurors required to be uninvolved in cases by the 18th century. This system was explicitly created to counter the whims of powerful individuals, fostering a peer-based justice that dilutes prejudice.

In recent years, concerns about judicial activism underscore why juries remain essential. UK judges have faced accusations of injecting political ideologies into rulings, from branding them “enemies of the people” in media storms to specific cases where leniency or decisions appear ideologically motivated. Examples include rulings on immigration, climate issues, and criminal sentencing that critics argue prioritise activism over neutrality. Scrapping juries would amplify this risk, handing more power to potentially biased judges and eroding the democratic check that juries provide. Remember all Judges have to be signed up the DEI ideology before they can sit in judgement.

A Call for Secular Sanity

Allowing faith to steer policy decisions like jury reforms isn’t just incompatible with effective governance, it’s a recipe for division and inefficiency. As Lammy and Mahmood’s statements illustrate, blending religion with law invites conflicts that could yield poorly crafted legislation. Meanwhile, practical fixes like utilising empty courtrooms and reallocating funds from bloated aid and immigration budgets offer a path to true justice for everyone, regardless of faith.

It’s time to prioritise evidence over evangelism, preserving the impartiality that has defined British justice for centuries. Otherwise, we risk a system where belief trumps fairness, to the detriment of all.